Emphasizing the “E” in ESG through Corporate Carpooling

Companies are constantly being pressured from all sides to raise the bar when it comes to their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) standards. But how can they do this effectively? Let’s stop looking toward distant rainforests earmarked for carbon offsetting and instead focus on smarter, more efficient use of the resources we already have.

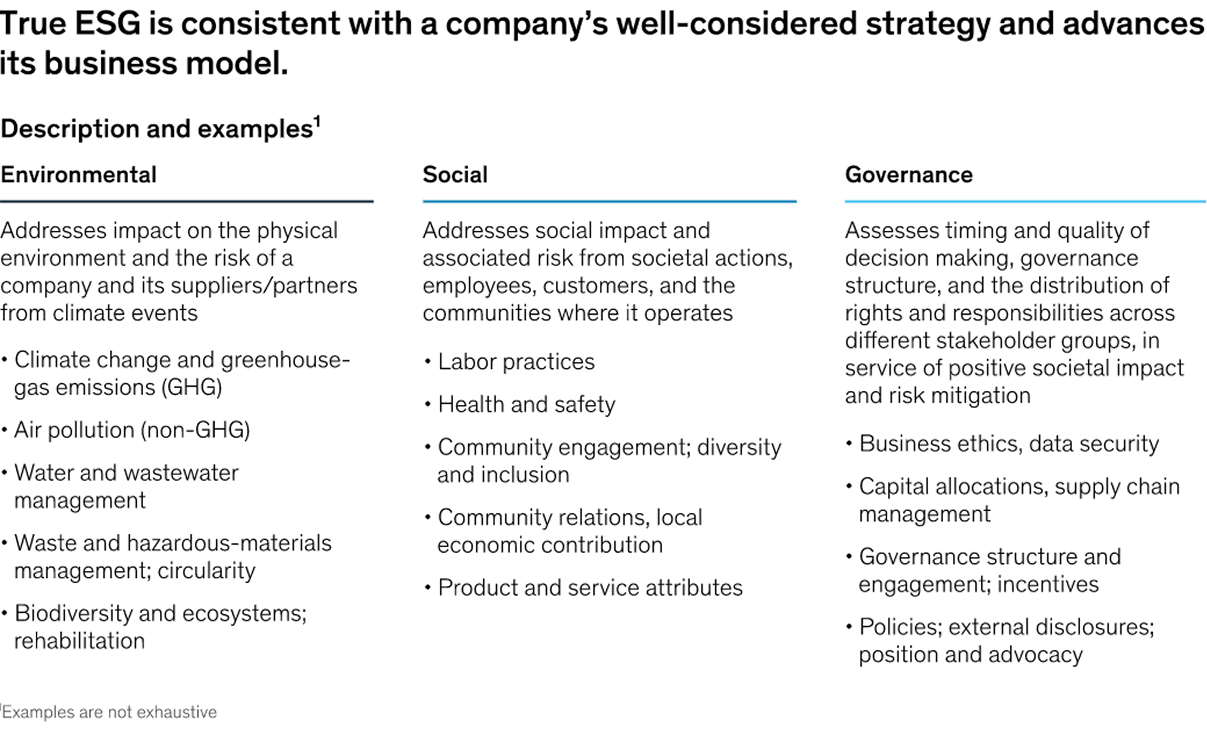

What is ESG?

It’s all too easy for the word “sustainable” to get lost in a sea of exaggeration and greenwashing. We see it — along with its many synonyms like eco-friendly, green, and environmentally conscious — everywhere, largely due to high demand. But it’s not just “Greta-types” and hippies advocating for change anymore. Corporate managers — whether they like it or not — are also involved. From a business perspective, these sustainability demands are now typically summarized under the umbrella of ESG: Environmental, Social, and Governance.

ESG has become the new holy trinity — guiding companies beyond pure financial growth toward more sustainable horizons for both society and the planet. Today, the private sector is under pressure from all sides — investors, politics, market competition, and consumers — to act more sustainably. Meanwhile, the term “sustainability” is being given more measurable, synchronized parameters through ESG frameworks.

From the world’s three largest rating agencies (S&P, Moody’s, Fitch) to the Big Four accounting firms (Deloitte, EY, KPMG, PwC), ESG has become a top priority. The trend is visible across companies — according to a 2022 McKinsey report, 90% of S&P 500 companies now publish some form of ESG reporting. But it’s not just the private sector moving voluntarily in this direction. Consumers are showing increasing demand for eco-conscious products — particularly among younger generations, who are quickly becoming the dominant consumer segment. According to Forrester (2022), more than half of consumers agree that it’s worth paying extra for sustainable or eco-friendly products. PwC (2021) found that 83% of consumers believe companies should actively strive to improve their ESG performance.

Let’s look at this from a different angle — focusing on regulations, public administration, and international organizations (while leaving out the scientific community for now). The UN-brokered Paris Agreement and the European Green Deal both bind their signatories to ambitious climate mitigation goals, impacting policy at both national and municipal levels. If a company wants to stay relevant and competitive, ESG reporting is no longer just a “nice to have.”

“ESG must be embedded in a company’s DNA — it can no longer be an add-on.”

Reporting on ESG is undoubtedly more nuanced than financial reporting. Numbers are absolute — they balance or they don’t. Environmental, social, and governance metrics are qualitative by nature, and therefore more complex to assess. Moreover, ESG is still a relatively new framework. Its reporting lacks universally accepted rules and takes place in a competitive environment, where companies are racing to meet KPIs as efficiently as possible — the nature of an open market.

Carbon offsetting

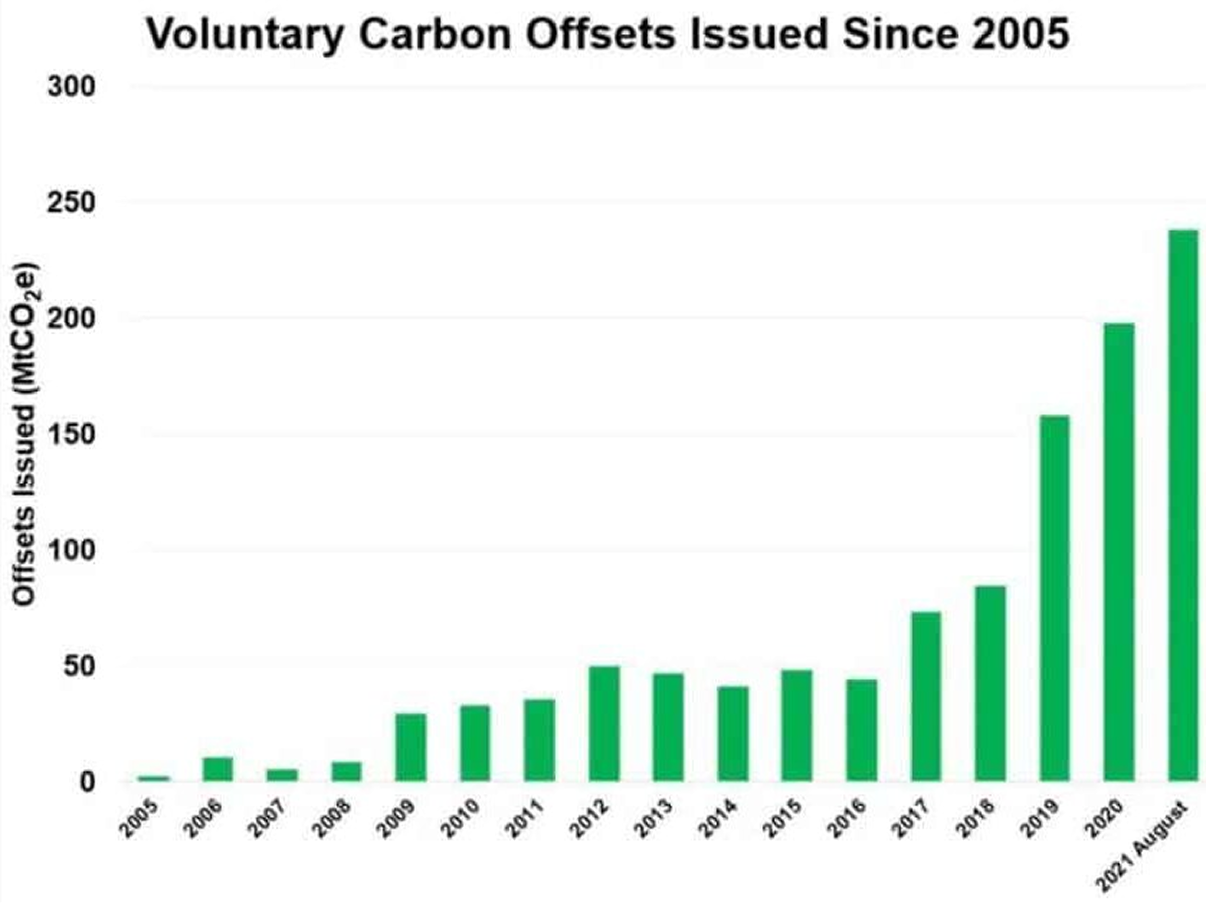

One way companies attempt to fulfill the ”E” in ESG is through carbon offsetting — compensating for their own emissions by supporting external projects that reduce carbon output, such as reforestation or renewable energy initiatives. The carbon market has been around for some time. The Kyoto Protocol, signed in 1997, is often cited as its origin. Since then, the market has grown, with third-party organizations helping companies calculate their carbon footprints and validate offsets. Examples include The Carbon Disclosure Project, The Gold Standard, or initiatives under organizations like the World Economic Forum and the International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation.

As the market has grown, so too has criticism. Some projects have been accused of functioning as licenses to pollute. Others have been exposed as fraudulent, unnecessary, or even harmful — like projects that were already self-sustaining, turned out to be unsustainable over time, or merely shifted emissions elsewhere. In general, the carbon offsetting market is often criticized for allowing companies to avoid responsibility for reducing their own internal emissions.

Carbon insetting

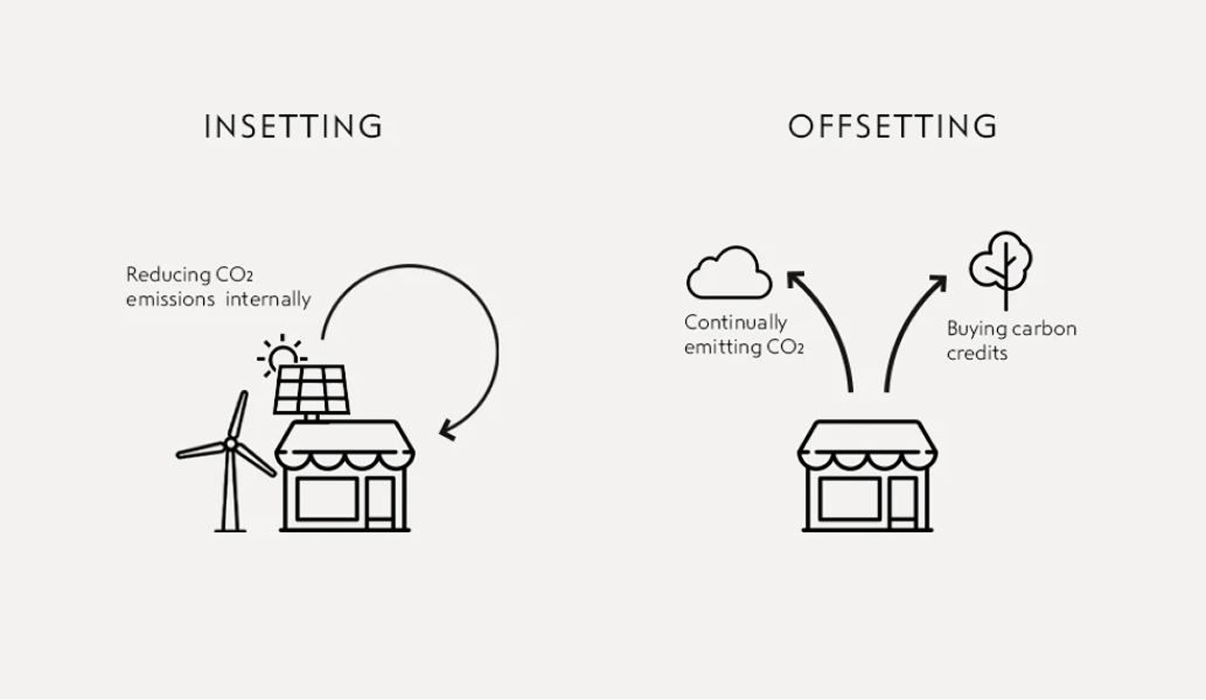

Zooming out to the broader “E” in ESG, flaws in carbon offsetting create space for a better solution. It’s rare for any new system to launch without needing fixes, and here’s a key one: shift from external offsetting to internal emissions reductions — carbon insetting.

Carbon insetting refers to reducing emissions within a company’s own operations. This could include adopting energy-efficient technologies, implementing circular economy practices, or transitioning to more sustainable modes of employee transport. While some industries (e.g., software) find this easier than others (e.g., manufacturing), internal reduction should always be prioritized over external compensation.

It may sound overly optimistic — as if waving a magic sustainability wand could produce large-scale change — but innovation and technology are moving fast. And innovation doesn’t always mean reinventing the wheel. Often, it’s about using existing resources more intelligently. Such optimization can be organized and implemented through digitization, automation, and data utilization, which are more accessible than ever.

Focusing on Transportation

One impactful area for improvement is transportation. Regardless of the industry, employee commuting is a key focus area. Road transport is one of the largest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions. In addition, cars bring with them noise pollution, take up valuable urban space, and contribute to road congestion, stress, and decreased quality of life.

Transportation accounts for 26% of total GHG emissions (Eurostat, 2019). The most common way to commute to work is by car — more than walking or public transport (Fleet Europe, 2019). Commuting to work is the #1 reason for driving (Eurostat, 2022). Cars are highly underutilized — average occupancy is 1.4 people per car. Cars are parked 96% of the time.

There’s enormous potential for innovation here — without extra spending, significant risk, or forcing people too far out of their comfort zones.

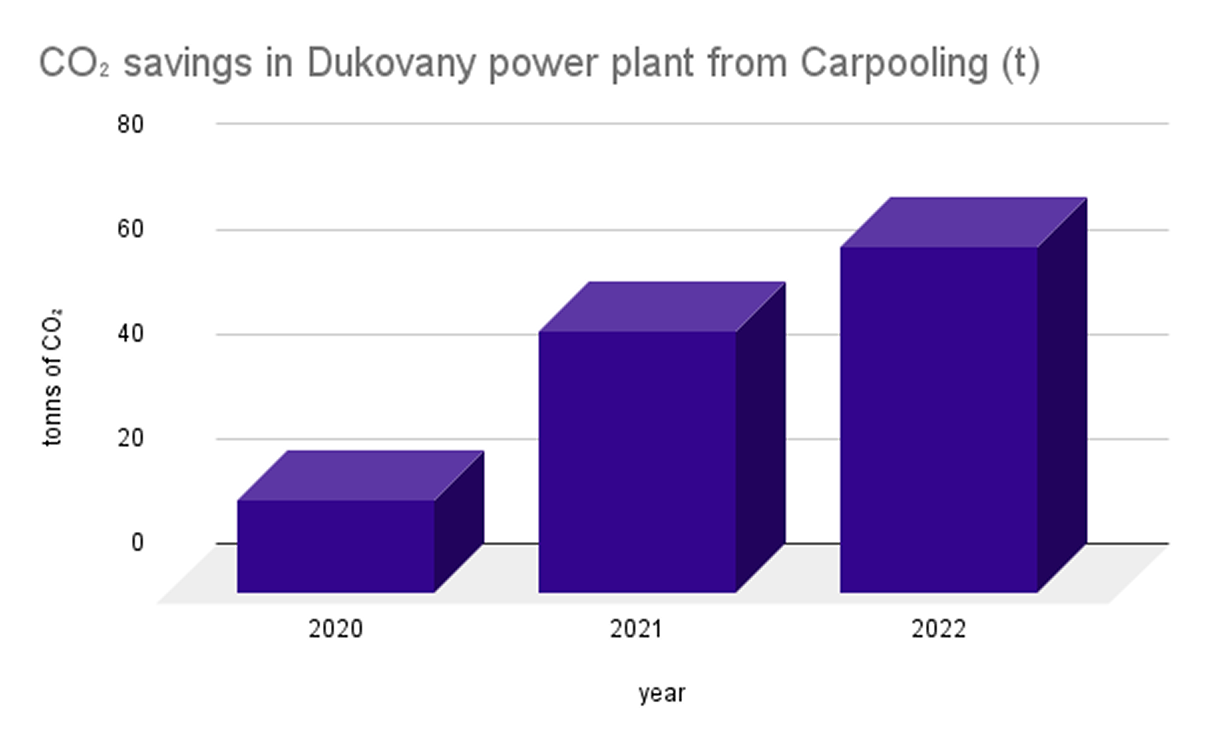

In 2021, ČEZ, a leading energy provider in the Czech Republic, implemented the Yedem Carpooling app for around 2,000 employees and external contractors at the Dukovany Nuclear Power Plant. The app made it simple for employees to share their commutes, helping them cut commuting costs and reduce corporate CO₂ emissions by 66,231 kilograms in 2022.

Why should corporations dive into carbon credit markets and distant rainforests when practical, impactful solutions are already within reach? Before leaping into new innovations, let’s look closer to home — and make better use of what we already have.

Be One Step Ahead

Subscribe to our newsletter for tips on handling company mobility and parking.

We Help Companies

Get Company Parking & Commuting Under Control

With our smart system for fair parking & commuting management. A triple win — for the company, your colleagues, and the planet.